- Home

- Brian Sammons

The Dark Rites of Cthulhu Page 2

The Dark Rites of Cthulhu Read online

Page 2

If I hadn't known Jake better, I might have thought he was about to take a powder. Then I heard it, too—distant chanting, getting louder.

"Where the fuck is it coming from?" I whispered, suddenly afraid to raise my voice. The chanting got closer—a strange, guttural cacophony that contained no words of any language I could recognize. At that point I wasn't even sure that human vocal chords were capable of making the sounds we heard—yips and cries, chirps and whistles intermingled with bass drones and harsh glottal stops. The whole effect chilled me to the bone, exasperated by a sudden blast of cold air that swept through the room like a gale.

"Somebody opened a window," I said.

"I don't think so," Jake replied, and pointed into the left-hand corner of the room.

At first it was just a darker shadow that seemed to suck the light away, leaving only bitter cold behind. My eyes strained to make out detail as the chanting rang in my ears and the room vibrated in sympathy. The light fitting swung lazily in time.

My whole body shook, vibrating with the rhythm. My head swam, and it seemed as if the walls of the cellar melted and ran. The light receded into a great distance until it was little more than a pinpoint in a blanket of darkness, and I was alone, in a cathedral of emptiness where nothing existed, save the dark and the pounding chant.

I saw stars—vast swathes of gold and blue and silver, all dancing in great purple and red clouds that spun webs of grandeur across unending vistas. Shapes moved in and among the nebulae; dark, wispy shadows casting a pallor over whole galaxies at a time, shadows that capered and whirled as the dance grew ever more frenetic. I was buffeted, as if by a strong, surging tide, but as the beat grew ever stronger I cared little. I gave myself to it, lost in the dance, lost in the stars.

I don't know how long I wandered in the space between. I forgot myself, forgot Jake, dancing in the vastness where only rhythm mattered.

After a while I dreamed. I dreamed a funeral—an open coffin where Jake's pale face stared up at me, a face I could barely see through my tears. I stretched out a hand to touch his cheek.

A gunshot brought me back—reeled in like a hooked fish, tugged reluctantly through a too tight opening and emerging into the blazing light of a cold cellar.

Jake stood in a firing crouch, emptying a clip into the corner. I drew my own gun and joined in, despite not being able to see anything but darker shadow. My ears rang, almost deafened by the shots in the close confinement. All too quickly my trigger pulled on empty. The echoes died away leaving dead silence behind.

Jake and I stood in a quiet, empty cellar that suddenly felt warm and stifling. We took one look at each other and headed for the steps at a run. He beat me to it, just, but I was level by the time we barrelled through the hallway and stumbled, almost fell, out into the driveway. A blanket of cold stars mocked us from on high as we drove off, leaving a squeal of tires in our wake.

"What the fuck just happened?"

O'Hara's bar again, and more of the black stuff, helped down with whiskey. Jake hadn't spoken since we left the cellar, but at least his hands stopped shaking as we headed into the second pint of Guinness.

"Magician's tricks and fucking hocus-pocus," he said. "That's what fucking happened. I told you there was something hinky going on, I fucking told you."

What I'd seen—and felt—back in the cellar was a bit more than hinky, but I knew when to keep my mouth shut, if nothing else.

"We're onto something," Jake said. "Somebody just tried to warn us off."

"Actually, I think they succeeded," I said, and got more of the Guinness inside me, trying to make a warm spot in a body that still held too much memory of dancing a cold empty vastness.

Jake took out the small notebook—I'd forgotten all about it, but he'd had it in his pocket the whole time.

"This is it," he said. "This is the thing that will crack the case open for us."

I wasn't sure where he was getting his certainty, but I trusted his instincts. He started to rifle through the pages.

"Maybe we should just leave it alone?" I said. "I saw something back there. I…"

"I don't want to know," Jake replied. It wasn't fear in his eyes this time—it was pleading. "Whatever we saw, it was just a trick. What else could it be?"

That was a question I asked myself all the way home. I fell into bed, but sleep was a long time in coming. When I finally drifted off, I fell into dreams of dancing galaxies, naked women lying on crudely carved circles, and Jake's dead eyes staring up at me through my tears.

I didn't feel rested on wakening, and when I got to work we caught a drive-by shooting that took us most of the morning to wrap up. When we finally got a quiet minute back at the precinct, Jake pulled me aside next to the coffee machine.

"I showed Kaspervitch the notebook. He says it's a simple substitution cipher. He's working on it now. We should get the gen in an hour or so."

"And then what?" I asked. I was weary. I couldn't see an end on Jake's current path that I liked, and I kept seeing that last dream, of him in the coffin. I started to get a real bad feeling, and what I wanted more than anything else was to just lose myself in the daily grind and forget all about the Mitchell case. But Jake was my partner, and that bought him a lot of slack. I decided to back his play—for the time being at least.

He hadn't noticed my reticence.

"I told you—we'll crack this case wide open. We're onto something. I feel it in my water."

All I felt in mine was cold, a deep chill that even copious amounts of black coffee wouldn't shift. Jake whispered something as we went back to our desks. I didn't quite catch it, and didn't know how important it would prove.

"I've seen it."

"It's a diary," Kaspervitch said, dropping the notebook on Jake's desk and making Jake's fifty disappear into an inside pocket. "Dates and places, I'm guessing of some kind of business meetings, for a lot of the names in his email contacts turn up in there too. But if they are business meetings, the times and places are off—unless I've made a mistake, all these meetings take place in quiet spots, in the middle of the night."

Jake looked up at me and smiled.

"See—I told you it was hinky."

He turned to Kaspervitch.

"So when's the next one penciled in?"

"Two days’ time—but he won't be there, will he?" Kaspervitch said.

"He won't. But we will," Jake replied. He had his game face on and the bit between his teeth. Nothing I could say now was going to make any difference. All I could do was tag along, and hope I could prevent the coffin dream from ever coming to pass.

The Thursday meeting was due for two in the morning in a disused warehouse in the docks. Jake and I got there early, around midnight. We parked well away from the place and walked in through the alleyways of derelict offices and factories. Both our fathers had worked here, way back when, and as kids we'd run together through these same docks, filled then with workmen and noise and vitality. Now they were as dead as the cellar beneath the Mitchell house, and damned near as cold. We took up a spot in the girders that made up what was left of the rafters of the warehouse, and tried to make ourselves comfortable for what might prove to be a lengthy stakeout.

Jake was quiet, scarily so, for I've rarely met a more voluble man, but he seemed content to sit and watch. He wouldn't allow any discussion of the events in the cellar. I couldn't really blame him for that—but I also couldn't help but wonder whether he had seen a dream of his own—and whether he might have been looking down at me in a coffin in his version.

My butt was starting to get numb from the cold seeping up through the girders when we finally saw some action. We were alerted firstly by the slam of car doors—two followed by a third a minute later. After a delay, three men, dressed in long, hooded robes that might have been comical in another situation, walked into the warehouse from the west-end and immediately started drawing diagrams and circles on the floor. The end result was all too familiar—it seemed to perfectly match the one that had been

etched beneath Mrs. Mitchell's dead body.

I realized I was holding my breath, waiting for something—distant chanting maybe, or another vision of the cold depths of space. What I didn't expect was for one of the three figures to stand in the center of the diagram, turn, and look straight up at our position.

"You can come down now," a deep male voice said. "The show's about to begin and you'll get a better view from here."

Jake didn't seem in the slightest surprised by the turn of events, leading me to wonder again what it was that he had seen in our time in the cellar. I was still wondering as we clambered down through a tangle of metal and girders to the floor of the warehouse.

The tall robed man was so polite it was almost surreal.

"Welcome, gentlemen," he said. "We've been expecting you."

"You saw it in advance, didn't you?" Jake said. "That's what you do—you use some kind of new trick to see what's going to happen."

"Oh, it's not a trick, I assure you," the robed man said. "And it's not new either—the Gatekeeper has been showing people the way since time began. You'll see for yourselves soon enough."

"I've got no intention of seeing any more," Jake said. He drew his gun and aimed it directly at the robed figure's chest. The other two—neither of whom had yet said a word, stood several paces further back, but showed no sign of getting involved.

"Jake," I whispered. "We can't do anything here. We've no proof of anything."

Jake waved his pistol towards the tall man.

"He did it—I know he did—he killed the Mitchell family."

The tall man laughed.

"Is that what this is about? I'm afraid you have it all wrong. Mitchell saw what needed doing at our last meeting. His wife was going to die—he saw it, and he knew it—that's the way it works. Once something is seen, it cannot be changed. Poor Mitchell couldn't handle it. He snapped—and you saw the results. And of course, his poor wife died anyway—such a shame."

He didn't sound in the slightest bit concerned, either at the death of Mitchell and his family, or by the fact he had a gun pointed at him.

Jake's earlier calm was rapidly being replaced by anger.

"That's not what happened—there's no way Mitchell could have done it—his gun was in the cellar."

"Oh, I did that," the tall man said casually. "I had to, you see—I saw it, so it had to happen. And I think I'm beginning to understand why it had to happen. It brought you here, to this place, this time. It brought you to the Gate. Yog-Sothoth has something for you to see."

We'd just taken a jump—another one—into the Twilight Zone. This wasn't going the way either of us would have predicted. Or rather, not as I would have predicted, for Jake seemed to know exactly what he was doing. He raised his gun.

The robed man drew a knife from up his left sleeve—a long curved thing with writing carved along the length of the blade.

"Put down your weapon, sir," Jake said.

"I assure you, it's purely ceremonial," he said, and raised it above his head.

"Put down the weapon or I'll shoot."

"You'll do what you have to do," the man said sadly. "I've already seen it."

He lifted the knife high, stepped forward and let out a yell.

"Ia!"

Jake put two bullets in him.

The tall man fell to the ground, grunted twice and coughed up blood all over the chalk circle.

Jake stood over the body, eyes glazed as if he was not really sure what he'd just done. I wasn't sure what to do about it—by rights I should have hauled him off downtown, but he was my partner—I trusted him. I just hoped I was going to be able to believe his reasoning.

As it turned out, I didn't have time to think. A colder chill blew through the warehouse, and behind it came the first distant sounds of chanting.

"Step out of the circle," one of the robed figures said. "Please, step out of the circle."

I took a step back—all that was needed to get me beyond the widest extent of the drawing—but Jake stood his ground, standing over the prone robed body.

The chanting got louder, the same dissonant mixture of singing, yips and screams we'd heard in the cellar.

"Jake—I think you should get out of there."

"Don't worry, pal," he said, grimly. "I know what needs doing—I've seen it."

The cold bit at my bones, and the chanting rose to echo and ring all around the warehouse. Something shifted—I can't describe it any better than that, and that's exactly what if felt like—a shifting to somewhere subtly elsewhere—or elsewhen.

It started small; a tear in the fabric of reality, no bigger than a sliver of fingernail, appeared in the center of the circle above Jake's head and hung there. As I watched, it settled into a new configuration, a black oily droplet held quivering in empty air.

The walls of the warehouse throbbed like a heartbeat. The black egg pulsed in time. And now it was more than obvious—it was growing.

It calved, and calved again.

Four eggs hung in a tight group above Jake's head, pulsing in time with the rising cacophony of the chanting. Colors danced and flowed across the sheer black surfaces, blues and greens and shimmering silvers on the eggs.

In the blink of an eye there were eight.

I was vaguely aware of Jake shouting, but I was past caring, lost in contemplation of the beauty before me.

Sixteen now, all perfect, all dancing.

The chanting grew louder still.

Thirty two now, and they had started to fill the warehouse with a dancing aurora of shimmering lights that pulsed and capered in time with the throb of magic and the screams of the chant, everything careening along in a big happy dance.

Sixty-four, each a shimmering pearl of black light.

The colors filled the room, spilled out over the circle, crept around my feet, danced in my eyes, in my head, all though my body. I gave myself to it, willingly. The warehouse filled with stars, and we danced among them.

I strained to turn my head towards the eggs.

A hundred and twenty eight now, and already calving into two hundred and fifty-six.

Jake had tears in his eyes as he looked at me.

"This is how it has to be," he said.

The protective circle enfolded what I guessed to be a thousand and twenty four eggs. Jake lifted his gun and emptied the clip into them.

Several things happened at once. The myriad of bubbles popped, burst and disappeared as if they had never been there at all. Jake screamed—a wail that in itself was enough to set the walls throbbing and quaking. Swirling clouds seem to come from nowhere to fill the room with darkness. Everything went black as a pit of hell, and a thunderous blast rocked the warehouse, driving me down into a place where I dreamed of empty spaces filled with oily, glistening bubbles. They popped and spawned yet more bubbles, then even more, until I swam in a swirling sea of colors.

I drifted.

When I got back—was given back—to what passes for reality, thin daylight lit the floor of the warehouse. There was no sign of the two robed figures—nor of the body of the man that Jake had shot. The chalk circle on the floor, and any blood that had been there, had been scuffed and scraped into the dust so much that any forensics gathering would be almost impossible.

Jake lay on his back, dead eyes staring up at me.

I didn't shed a tear in the warehouse, but the funeral is later today. I have to do my best not to cry, but I fear that I will.

This is how it has to be.

Dead Man’s Tongue

By Josh Reynolds

“A man enters a room, carrying a strangely proportioned package. He is not seen again, until his screams alert his fellow tenants in the boarding house as to his distress. The door is busted open, and not one, but two bodies are found. The origin of the first is obvious, but the second—ah, that’s the mystery, ain’t it, Carter?” Harley Warren said. He rubbed his hands together gleefully and sank down onto his haunches just outside of the room in question.

/>

“A mystery we should perhaps leave to the police, don’t you think Warren?” Randolph Carter asked nervously. He and Warren were a study in contrasts. Carter, the tall, thin lantern-jawed expatriate from Massachusetts, and Warren, the short, stocky cat-eyed South Carolinian, made for an odd pair. Carter often found himself wondering how and why he was still in South Carolina, in Charleston, and still trundling in Warren’s oft-disturbing wake. Times like these only made such moments of introspection occur more frequently.

“Seeing as the police are the ones who came to me about this here little conundrum, I’m going to go out on a limb and guess that they wouldn’t be at all grateful in that regard,” Warren drawled. Carter glanced back down the hall, where several uniformed Charleston police officers stood nervously. They'd come knocking sheepishly on Warren's door, and had escorted them to the boarding house where they now stood. Warren had an odd relationship with the local constabulary. For the most part, they were inclined to ignore him. But sometimes, something happened and men would come, seeking quiet consultation or, as in this case, something more active.

Carter had first visited Warren’s Charleston residence seeking a consultation of his own. Then, as now, Warren had displayed a level of occult competency that Carter found both comforting and not a little frightening. Carter had sought relief from the night-terrors that flapped and squirmed and tickled his soul with rubbery talons and scorpion tails and Warren, opium-numbed and erratic as he was then, had guided him through the labyrinth of dreams that he had been trapped in. But he had found relief from one nightmare only to be propelled along new avenues of dread in the months since. Warren had set aside the dragon-pipe at Carter’s insistence, but remained erratic; indeed, he had become almost predatory since Carter had moved in to the strange house on the Battery.

Warren now hunted the unknown through yellowed pages and across rolls of papyrus and cowhide, looking for any gleanings of old knowledge left behind. He looted tombs-or paid others to do so-and collected the detritus of centuries with compulsive glee. Warren collected the hideous and the beautiful in equal measure, and Carter occasionally suspected that he, too, was a part of his friend’s collection, in some odd way. But the purpose of that collection still eluded him. Warren was hunting something, and Carter feared the day that he finally caught it.

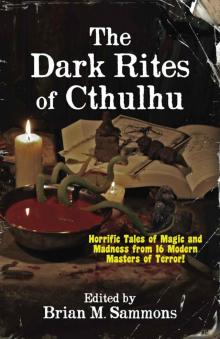

The Dark Rites of Cthulhu

The Dark Rites of Cthulhu