- Home

- Brian Sammons

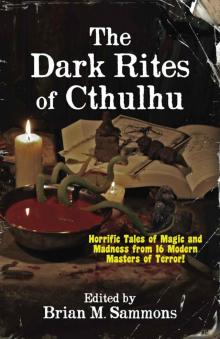

The Dark Rites of Cthulhu Page 24

The Dark Rites of Cthulhu Read online

Page 24

There are windows, but they don’t admit daylight. None of the frames are the same size, and none of the panes have straight edges. Some of the glass is clear and some clouded, or frosted nearly opaque. The stained glass portions are jewel-toned, marbled, and swirled. They glow, as if from within, as if by their own eerie, eldritch illumination.

The mindhouse’s acoustics are as peculiar as the rest of it. Sometimes a whisper will resonate like a gunshot; sometimes the loudest shout vanishes into thin air. It might be silent as a tomb at midnight in that room, or the very space itself might hum with a sourceless vibration, a deep bass-note from everywhere and nowhere. Footsteps echo as if the space beneath is a hollow chasm… or they thud as if on solid ground… or they are swallowed up as if absorbed.

Occasionally, we hear chimes. Silvery, horrible, musical yet atonal chimes. A few times, it’s seemed like distant voices answer back, murmuring in multitudes. Once – thankfully, just that once – we heard a wet, heavy grunt and a slithery shifting I could have done without.

You might think that it’s a weird, creepy place for asylum inmates to be brought for groups, and you’d be absolutely right. As crazy as I was my first time there, I wasn’t so crazy as to realize that it very much was not the typical setting of durable stain-resistant carpet, fluorescent lighting, and folding chairs. No. I’d seen plenty of rooms of that kind before. The mindhouse was different, very different, right from the first.

Similarly, Doctor Hasturn is not the kind of psychiatrist I’d typically encountered before arriving at Evergate. Tall and slender, pinch-faced… jaundiced of aspect and bloodshot of eye, as the poets might put it… nothing of the caring, kindly counselor or the wise, nodding sage here. We never talk about our mothers, or our unresolved issues with potty-training and fears of abandonment. We don’t discuss our anxieties or neuroses; lines like “mm-hmm and how does that make you feel?” are never said.

Dreams, though, we do discuss. Dreams, according to Doctor Hasturn, are the secret speech of the universe. They aren’t to be analyzed with trite symbolism, nothing so new age or Jungian as that. They are deeper messages, far deeper than the sub- or unconscious. They are from beyond, from outside, from the primal currents of the under-psyche.

In the dreams, sometimes, the nonsense syllables of our glossolalic therapy chants aren’t such nonsense after all. They begin to seem like words, like a language just beyond our comprehension. I’ve asked the others and we all agree… they’re almost within grasp. Almost.

And sometimes – when Doctor Hasturn has cots brought into the mindhouse, to conduct sleep-studies on us there – sometimes the dreams become much more than dreams. Much other than dreams.

Once…

I won’t say it was a vision, because that would be insane. But it was very vivid, the most vivid dream I’ve ever experienced. Tangible. Tactile. Each sensation true to my senses, so real in its unreality, so unreal in its reality.

I heard the chimes, ringing and clinking, pure as glass, dull as bones. Papery reeds, thin as spider-legs, hissed a susurration in a hot and airless breeze. I felt the dry, pebbled ground beneath my bare feet, my steps kicking up gritty puffs of yellow dust. It smelled sour. Sour and yellow and old. Tickling my nose. The taste of it settling, dry, so dry, on my tongue. The screaming stars wheeled above me, unfamiliar and hideous constellations viewed through a murky-green veil of sky like dead sea-water. What passed for a sun hung bloated and pustulant above an endless horizon, silhouetting the corroded ruins of some ancient city.

Or palace.

Or temple.

Or tomb.

Doctor Hasturn questioned me extensively when I awoke. Had I seen anyone? Spoken to anyone? Were there landmarks I could name? Had there been any living thing besides the papery reeds? Could I plot a star-chart of those strange constellations?

I later learned from Nathan that I was not the first to have such a dream. In his, there’d been a road, cart-tracks having worn ruts in the dirt, and a pile of stacked stones like a mile-marker. Some of the others had glimpsed sticklike figures moving in the distance, wearing tattered garments of coarse brown cloth.

It doesn’t mean anything, of course. They weren’t actual visions of an actual, real place. Let’s not go nuts, here. Subliminal suggestion, mass hallucination, any of that’s unsettling enough without…

Though, now that I think about it, Doctor Hasturn did start questioning me even before I’d really begun describing my dream. Pressing for specific details about things I don’t remember mentioning. Asking if I’d noticed marks on my skin, for instance, painted symbols, or designs like henna tattoos.

If dreams are messages…

And messages have to come from somewhere…

If the mindhouse is the focal channeling point of a psychic vortex, as Doctor Hasturn says, then what is on the other side?

On the outside?

Outside of ourselves, outside of everything?

What else might be there?

What… entities?

What feeds upon our mental chaos?

Nothing good, I can tell you that much.

Dark forces? Evil powers? Otherworldly elder beings who will one day shatter the dimensional barriers, enslaving or destroying us all?

Whatever happens, it’ll take far longer than our meager human lifetimes to reach the tipping point. Therefore it isn’t our problem, right? Because we’re such small and insignificant portions of the greater scheme of things. From the big-picture perspective, I mean.

From our individual, personal perspectives…

It takes away our madness. We have our own minds again, our own thoughts and lives and souls and selves.

Yet we’re helping to empower and strengthen something. Something dangerous. Destructive. Something other. Something Outside. Each contribution, however slight, pushes this world toward the brink. The clearer we get, the closer we all come… the closer to crossing that threshold.

Save our sanity, doom humanity.

Kind of catchy.

If horrible.

I know how this sounds. How crazy it all sounds. But I’m not crazy. Not now. Not anymore. My symptoms haven’t just been managed with medication or suppressed by behavioral tricks. They’re gone. Gone.

I’m not expecting you to believe me. I’m not asking for your forgiveness.

I just want someone to know. To understand why we do this.

Why we want, and need, the mindhouse.

Besides, it’s not like there aren’t others. Other mindhouses, situated at key points around the globe. A dozen more, at least.

It’s still not enough, though. When I think of all the people out there, suffering like I did… when I think of the families torn apart like ours was… when I think of all that pain, all that torment…

Wouldn’t it be wonderful to be able to help them?

To restore their sanity? To heal them? To spare anyone else from having to go through what I‘ve endured? I know I’d want to do what I could. I’m sure you would, too.

The thing is, you could. If you wanted to.

Doctor Hasturn showed me the articles you’ve written, the papers you’ve had published in the leading journals. You’re about to embark upon a brilliant international career, sure to make a lasting and memorable mark.

They’re calling you a prodigy, you know. The most innovative, intuitive and accomplished young architect of our time.

You should definitely come to Evergate for a visit. I’d love to see you again. I’m so proud. And, who knows? Maybe you’ll pick up a few new ideas.

The Half Made Thing

By T. E. Grau

“Let us sing, let us sing,

Of the Half Made Thing.”

Miles of rolling green rose and fell under a tight vest of mist that almost seemed alive with the way it clung to the low parts of each valley, creek bed, and sudden crevasse marked by dead Roman wall. These were clouds jealous of the earth, who came to dwell amongst man in this lonely part of Northumb

erland, and were therefore assigned living qualities. Moods, quarrels, secret pacts. You could tell the weather by the fog, the locals said, and sometimes the future. Today the mists said nothing.

Through this veil of milky white burst a pair of mares, froth flecking the rounds of their massive jawlines. Mudded haunches churned like pistons as they careened down a winding country road first hewn by occupying Norsemen that could accommodate only one vehicle at a time, which presently was a dark green carriage, accented in gold and piloted by a cloaked figure leaning expertly into his task.

Up ahead, a herd of sheep trundled from the fog and crossed the path, bumping into each other and mewling softly. The horses didn’t slow a step as they charged into the flock, which parted like a woolen sea of terrified sideways pupils and bleating tongues. One goat emerged from the group and stared defiantly at the carriage as it sped by.

Horseshoes forged from Birmingham iron clattered upon worn flagstones. Plumes of steam shot from the horse’s nostrils as the carriage came to a stop in front of a towering English mansion. Built a millennium past, it was more castle than home, covered in ill-tended ivy and shrouded by that dank mist which remained unmoved by the cold North Sea wind blowing in from the coast.

The carriage door banged open, and from it emerged Thomas Nevill, a once handsome man worn to sinew and worry by years of backbreaking labor in East London mills. He chafed inside his velvet waistcoat and baggy breeches, scratching at the lank, bone-colored wig that topped his high forehead, as if still adjusting to the stiffness of finery. The costume of a dandy.

His shiny buckled shoes slipped on the damp stone as he eagerly lowered the carriage stair, and with a dangerous creak to the axles, out stepped Marsila, Nevill’s short, stout, shockingly ugly new bride. Not even a thick layer of white pancake makeup could cover the pits and moles that assaulted her distended face, punctured by a pair of close-set yellow eyes that added a piggish quality to the horsiness of her appearance. She adjusted her pink-tinged wig, looked at the mansion and grinned, exposing a tiny row of rotted teeth. A fly buzzed around her mouth.

Nevill offered an arm to his wife, and they walked toward the house without a glance behind them, as Elias, an eleven year old boy, hopped down from the carriage and glumly shoved his hands into the pockets of his simple trousers. He obviously resembled his mother... a mother lost far to the south.

Elias looked back at the carriage driver, who watched him beneath the folds of his cloak, only the tip of his long nose providing evidence of a face underneath. After several moments of nothing passing between the two, Elias trudged away, veering toward the back garden. Behind him, the horses stamped their hooves on the flagstones, the impact ringing like gunshots sucked into the gloom that hid the sun above.

The tall grass snaked against Elias’ feet, soaking his pants and tripping him up. He stepped high and pushed through, inspecting the overgrown grounds along the side of the house. The trees looked too large, and not native to the British Isles, propped up on bloated tubers that gathered above the ground, providing hiding places within the tangle of roots. Great explosions of unruly shrubbery stood uncut for what must have been decades, and seemed to take the shape of monstrous, unformed creatures.

Suddenly feeling exposed, Elias moved closer to the house, running his hand along the greenish stone textured with the play of lichens. Coming upon a salt frosted window, he peered inside, framing his eyes with his hands to block out the diffused sunlight smeared gray by the fog. He saw nothing on the other side of the pane. Just a greasy darkness, veined with the swirl of memories that had nothing to do with him or his father.

In the sprawling back garden, accented by randomly placed trees and weathered statuary, Elias crunched through a dead flowerbed and stubbed his toe on a stone half buried in the sandy soil. Angry, he tore it from the ground and heaved it at a window on the second floor, puncturing the glass in a perfect silhouette of the rock, but not shattering the window. Nevill’s frowning face appeared above the hole, his expression cold. Elias looked down at the buckles on his wet shoes, a matching pair to Nevill’s, purchased by another family’s money. The boy remembered when his father would have thrashed him for such a transgression. Since the wedding, he only received that same, hollow look. Elias peered up at the window, but his father was gone. The boy searched for another rock.

Elias moved from room to dusty room, each one darkened by thick, pea green curtains drawn across the windows. All the furniture was covered by white sheets, like the lumpen mummies of fallen Titans. Each room, all the same. All furnished with the belongings of strangers. All covered in funeral shrouds.

Upstairs, he stood in the doorway of a cramped bedroom, smaller than the rest of the rooms. Servants’ quarters, most likely. The shattered hole in the window let in a breeze, which set the sheets flapping and undulating like white tentacles of jellyfish. There was other movement, too, but they were vague, only detected from the corner of his eye. Anything regarded directly was still. Elias smiled and dropped his bag next to the rock on the floor, surrounded by broken glass. This would be his bedroom, marked as it was. Elias believed in such signs, things that weren’t taught in mass. The way he saw it, one didn’t argue with the destiny of stone.

Lying on the floor of the second story hallway, Elias bounced a canvas ball off of the fresco painted on the paneled wall across from him, aiming for the comically large codpiece of a hulking jester set amid a Renaissance party scene populated by forest creatures dancing with their human companions. The clown’s four-pointed belled hat rose like sweeping horns above his head, a forked tongue lolling from his grinning mouth. Elias threw the ball at the wall, finding its mark, and the ball bounced back into his hand each time. He did this over and over, the dual thud of the ball finding a measured rhythm.

“Boy!” his father’s voice shouted from somewhere lower in the house.

Elias caught the ball and held his breath, waiting for an admonishment, but none came. In the silence, the thud of the ball echoed back at him. Two beats at a time. Like a sluggish heartbeat.

Half tempted to toss the ball again to arouse his father’s once-famous temper, Elias instead rolled the ball down the long hallway leading to the other end of the house, lit by a series of thin, ineffectual windows that fought to keep out slivers of pale light. The ball rolled along quickly, moving in and out of the rays of white, then suddenly stopped, half illuminated, half in the dark. Elias found this curious.

He got to his feet, walked to the ball on damp socks and picked it up. It felt suddenly heavier, like a cannon ball, and he struggled to bring it to his chest. He looked it over, and found it no different than when he had tossed it moments before. Readjusting his feet under the weight, the floor gave a little. He poked it with his toe, and found the boards pliable, soft. Elias dropped the ball, and it buried itself an inch into the wood. There was a shift behind him, and he shot a look back at the fresco on the wall, and found that the painting had changed, as it now showed the animals tossing the humans into a hole in the ground. And still the horned jester danced and grinned, his tongue wagging at the horrified faces of the figures falling into the earth. Before he could inspect this, a shadow passed across the slatted windows. He walked to one of the openings, turned his head to the side, and looked outside.

It was a view of the back estate grounds, but from a higher vantage point than he had earlier. The expanse of garden dotted with carved figures stretched to a stand of forest about quarter mile from the house. Something large jutted up from the ground in the middle, like a pointing fist. Beyond that, at the forest’s edge, a stone and plank gristmill moldered on the shores of a sludgy stream. Its ancient wheel, draped in algae, turned slowly.

In the dining room later that night, a brightly colored pinwheel spun in Elias’ hand, reflecting as identical spirals in his brown eyes. His mother had bought it for him in Brighton when he was just a wee lad. Half the size he was now, and smaller still by four. Elias blew on it, watching it spin, finding some

thing in the whirling, almost smelling the perfume of his mother’s hair in the feeble breeze it provided.

“Boy!” Nevill barked.

Jarred from his reverie, Elias peered down to the far end of a ridiculously long table, where his father glowered at him, embarrassed. He was always embarrassed these days, ashamed of himself and his son and his dead wife and everything the three of them had been before meeting the woman who had asked him to marry her after knowing him for two months. Elias put the pinwheel down. Marsila was seated at the head of the table. Nevill was to her right, more handmaiden than husband.

“I asked you to thank your mum for…” Nevill looked at Marsila for prompting, and she mouthed the words to him. “Our lovely new home,” Nevill finished, grinning with the accomplishment of a dimwit successfully reciting a nursery rhyme.

“Thank you,” Elias said.

“Mum,” Nevill said, finishing a sentence Elias would never, ever think, let alone say.

Elias looked at his father, who gripped his fork in a shaking hand, then at Marsila, who watched him with a curious expression. Finally, Elias sighed. “Mum.”

Nevill nodded and tucked into his meal, sawing at the slab of meat on his oversize plate. Marsila continued to watch Elias, draining a goblet of dark wine, sediments cascading down the side of the garish blue glass.

The trio looked tiny at the enormous table, which in turn looked miniscule set amid this sprawling dining chamber, its vaulted ceiling stretching two stories above them. Murals of naked humans frolicking with leering, piping satyrs covered the frescoed panels between massive wooden beams. The domestic help, silent and expressionless, deposited food and drink, and at an imperious wave from Marsila disappeared into the darkness of the house. Elias tried to learn their faces, and hopefully their names, but he found that as soon as they left his vision, they also left his mind, and he couldn’t remember nor distinguish between any of them.

Elias picked up a fork, and looked down at the whole fish staring up at him from his plate. Nothing had been removed prior to cooking, nor afterwards, and aside from the boiled smell, Elias half-expected the gawking creature to leap from the plate and flop its way toward the nearby sea. Hacking loudly and sucking mucous down her throat, Marsila stuffed a napkin into the front of her many layered dress and tore into her roasted game hen, chewing through bone and gristle and dangerously undercooked meat. Nevill dabbed at the juices that dribbled down her chin. Marsila grunted at him with pleasure, like a sow at the trough.

The Dark Rites of Cthulhu

The Dark Rites of Cthulhu